The US is urgently ramping up its missile production plans. The Pentagon, alarmed at the low weapons stockpiles the US would have on hand for a potential future conflict with China, is urging its missile suppliers to double or even quadruple production rates on a breakneck schedule, The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported on Monday. While ambitious on the surface, the move exposes Washington’s deep-seated anxieties.

The WSJ revealed that US military leaders are urging defense contractors to increase assembly of 12 critical weapons, including Patriots and long range anti-ship missiles (LRASMs). “An early request for information asked weapons makers at the June roundtable to detail how they could increase production to 2.5 times current volumes through steps taken over the following six, 18 and 24 months,” the report said.

The WSJ also noted that “the Army in September awarded Lockheed almost $10 billion to make nearly 2,000 PAC-3 missiles (a hit-to-kill interceptor) from fiscal year 2024 to 2026. The Pentagon wants suppliers to eventually pump out that same number of Patriots each year – nearly four times the current production rate.”

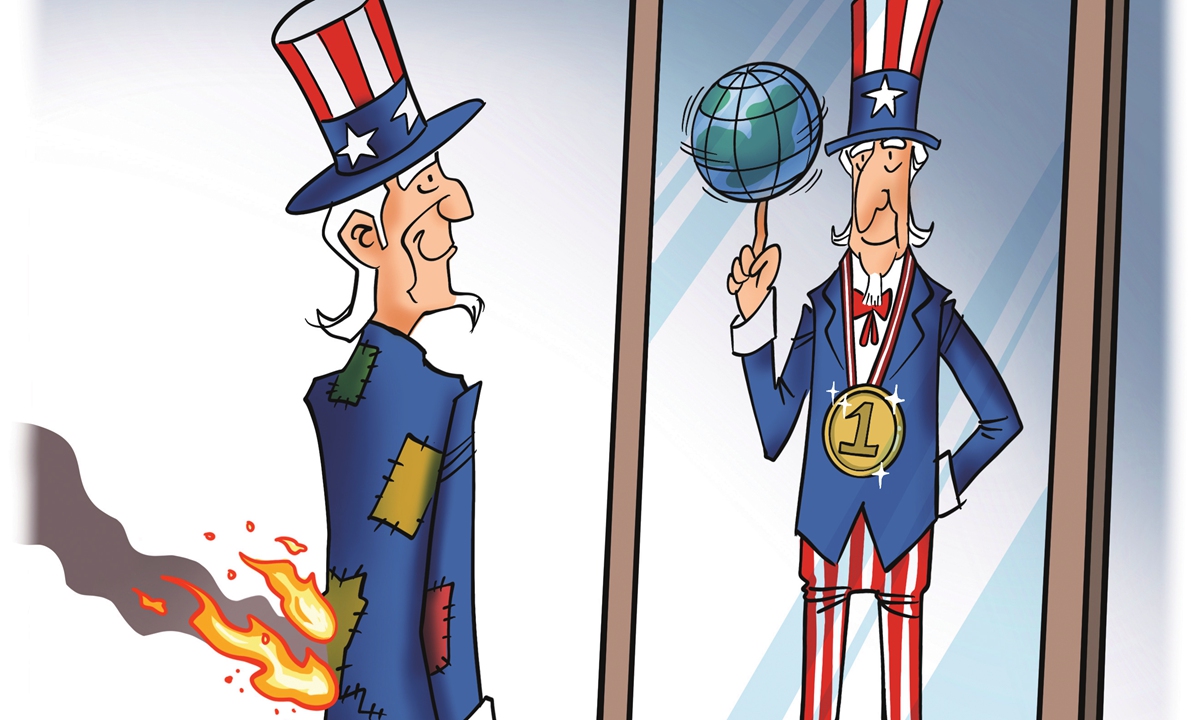

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and wars in the Middle East, the US military has grown increasingly concerned about its missile production capacity. Analysts note that Washington’s aim on pushing missile production is not only to replenish its own stockpiles, but to capitalize on global conflicts as a lucrative arms market. And China has become the most convenient “excuse” to stoke fears. China’s rapid advances in weaponry have led some observers to believe that the US has become uneasy, prompting a reevaluation of what “military advantage” the US still holds.

The WSJ report lays bare two pressing US anxieties. First, a shortage of missile stockpiles. Second, a crippling shortage in manufacturing capacity. When the Pentagon sought to ramp up missile production, “some people involved in the effort” responded bluntly with “unrealistic,” exposing the structural problem in US manufacturing and the gap between Pentagon ambitions and reality on the ground, Shen Yi, a professor of international relations at Fudan University, told the Global Times.

Amid these challenges, the WSJ reported that “the military also asked suppliers to describe how they might attract new private capital and potentially license their technology to third-party manufacturers.” However, this raised skepticism about how much this approach could truly boost US capacity.

Such measures may simply open the door for interest groups to profit. Despite massive annual defense budgets and procurement spending, US capacity still falls short because much of the funding is funneled into corporate profits rather than translating into real combat capability, Shen told the Global Times.

The US should realize that if it scaled back its global military interventions and proxy wars, the missile production shortage might never have become a problem in the first place.

The US also refuses to acknowledge that China’s growing military power is primarily aimed at protecting its sovereignty, security, and development interests. For instance, at the core of China’s sovereignty lies the Taiwan question. If the US did not interfere in China’s internal affairs or challenge its sovereignty, there would be no need for the US to worry about China’s defense development.

Yet ultimately, the US will have to confront one reality: portraying China as the “enemy” and rushing into an arms race won’t solve its own problems. As Zhang Xiaogang, a spokesperson for China’s Ministry of National Defense once said, “China has no intention to challenge any country. In fact, the worst enemy of the US is the US itself.”