Four years have passed since the attack on the Hillel Yaffe Medical Center hospital, an event that underscored the vulnerability of Israel’s health care system. Since the October 2023 events, Israel’s online environment has become a turbulent front: the country suffered 3,380 cyber‑attacks by the end of the year, representing a 2.5-fold increase compared to comparable periods in the past. Of those events, 800 were classified as having “significant potential for damage.”

4 View gallery

The cyber attack on Hillel Yaffe hospital disabled part of the hospital’s services for a period

(Photo: Elad Gershgorn)

According to the Microsoft Digital Defense Report 2025, Israel ranks third globally in the number of cyber‑attacks directed at it—second only to the U.S. and the U.K.—and absorbed 3.5% of all global attacks.

In the Middle East and Africa region, Israel is first, having taken 20.4% of all recorded cyber incidents in that region.

Facing the country are persistent adversaries like Iran, which directs approximately 64% of its global cyber‑activity at Israeli targets in order to gather intelligence, disrupt services and spread propaganda.

The attacks are carried out not only via vulnerabilities and exploits, but also by using compromised credentials resulting from breaches of other entities or by classic phishing attacks (social‑engineering based) which succeed in gaining unauthorized access to organizations’ systems.

Despite the constant presence of state‑actors (governments constitute 17% of global targets) the main motive behind the attacks remains financial: in 80% of cases the attackers sought to steal information, and in over half of cases (52%) the motive was extortion or ransomware.

Ynet spoke with Amir Preminger, CTO of the company Claroty which specializes in protecting critical infrastructure, to try to understand where we stand today vis‑à‑vis these cyber threats, and what the future holds.

Claroty published data on cyber‑attacks. Do the numbers you published reflect the full picture, and do they include only successful attacks?

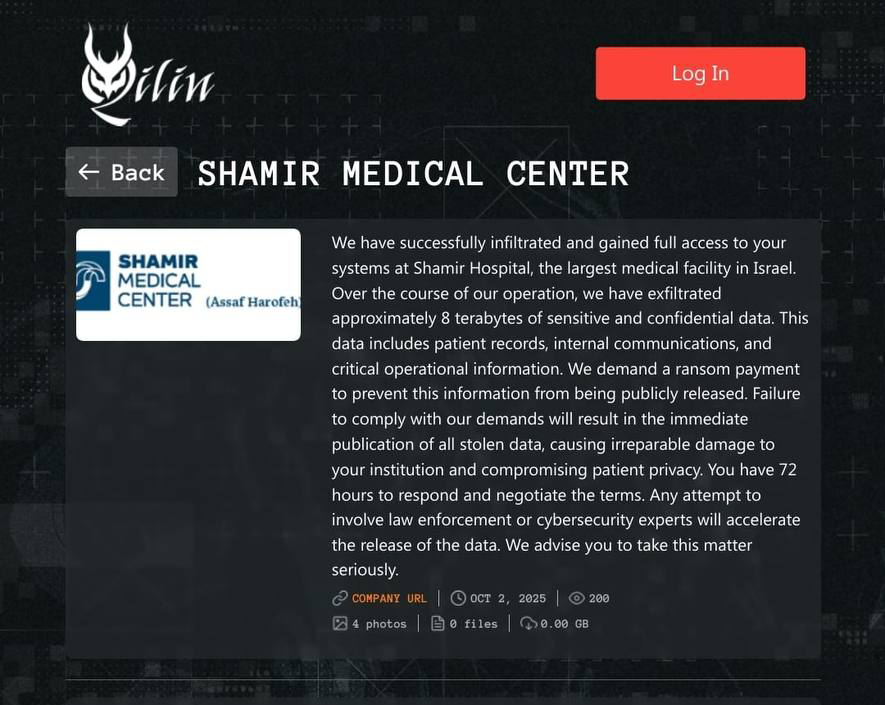

“It’s important to define what constitutes an attack. Our data comes mainly from publications by various attacker groups, either in formal media or on the dark web. We monitor the dark web, Telegram groups and forums in order to extract indicators of attacks that are definitely related to critical infrastructure, such as hospitals, and especially organizations under Claroty’s umbrella.

“We invest significant resources to ensure there are artefacts that indicate intrusion or theft of data (such as medical records or internal hospital servers). This is minimal validation, and what’s published is what we were able to extract.”

The data you published paints a particularly alarming picture for Israel. What is the significance of the fact that in the last 3 years more than 136 reported attacks were carried out in Israel by over 20 hacker‑groups? And how exposed are hospitals?

“These numbers require us to wake up. Of all the attacks reported in Israel in the last three years, 34 attacks, about 25%, were directly targeted at critical infrastructure. Worse, 8 out of 136 attacks, about 5%, were directly targeted at health organizations.

“Hospital networks are organizational networks in every sense, similar to a computing network in an insurance company or a factory. The threats are only increasing. Hospitals in Israel accumulate threats from hackers and activists who want to prove they succeeded in harming them, and their exposure level is similar to any other organization. However, due to digitization, hospitals are exposed to more external resources.”

What trends in attack methods do you identify, and what are the weaknesses enabling most of them?

“In recent years we have witnessed a significant rise in attacks demanding ransom (ransomware) and data theft. The attackers’ motive combines demand for ransom with a desire to damage reputation. Beyond the motive, the weaknesses that allow most of the intrusions remain basic, sadly: weak passwords and password reuse; neglect of software updates; and use of outdated protocols and software that are not considered secure.”

When speaking of state‑based attacks, is there concern that our medical records will find their way to hostile states, and what is the difference between a ransomware attack and a state‑sponsored one?

“The attacker’s motive is the key. There is a difference between a state campaign to steal information and ransom aimed at money or notoriety. State‑sponsored attacks can be divided into two types – the “red‑button” (shutdown) type, which uses a covert capability to take down, say, a hospital system.

“This is a one‑off event that is intended to create maximum impact. Cause patient harm, death or what is called maximal impact. The moment you activate it, the attacker raises awareness and may be expelled from the network. The incident at Hillel Yaffe, for example, disabled part of the hospital’s services for a period.

“The second type of attack is for information collection. A covert presence inside networks for gathering personal information. We probably haven’t heard about it because it doesn’t cause service disruption. As digitization grows, even private clinics use similar systems, making personal information more accessible.”

Is the current situation really “acceptable,” or is it worrying?

“It’s worrying. Things are being breached on a daily basis. We have no way of predicting attacks, and the only thing to emphasise is the need to continue investing in ongoing security. Attacks simply happen, it’s a matter of probability and timing.”

You spoke about artificial intelligence and enabling attack capabilities. Does AI create a gap between attackers and defenders, or do we have similar defense tools?

“It will always be a cat‑and‑mouse game. The capability has been given to both sides, but defense is always harder than offense. AI has significantly improved exploit‑time for a vulnerability, and allows an attacker, who previously did not have programming expertise or a certain platform, to acquire knowledge and use it at much larger scale and faster speed.”

Are there already smart agents capable of carrying out attacks autonomously?

“Yes, there are already a number of different agents that can do so. The difference from automatic tools of the past is that AI can make reasoned decisions. Instead of a simple scanning tool, AI incorporates decision‑making and learning ability which shortens time and increases the amount of information upon which it bases decisions.

“In the medical sector, using AI‑agents leads to much greater sharing of medical information, raising privacy questions. Moreover, these technologies create a new attack surface, and the problem is organizations rush to implement them without sufficiently understanding the security implication.”

Where is the cyber‑world headed in the coming years, in your estimation?

“If you ask me, we are heading in several directions. The first is increasing change via AI — organizations will need to share information with external parties (such as cloud‑services) who have the required resources. This raises difficult privacy issues.

“The second is a rise in the quantity of attacks and their complexity. The number of attacks is increasing trend‑wise, and the attackers are becoming more skilled. The third direction we will see the cyber‑world go is the need for protection beyond the ‘four walls,’ since the traditional organizational perimeter no longer exists.

“We will see more data exposure due to third‑party actors, and organizations will need to intervene in their partners’ security state. This required reciprocity will force all entities to improve their security capabilities.”

4 View gallery

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visits the National Cyber Command in Beersheba

(Photo: Kobi Gideon/GPO)

Where do we stand in terms of government regulation in the cyber‑domain?

“Government involvement in protecting private entities is very limited. Although Israel has serious cyber‑capabilities, its ability to enforce or transfer knowledge to industry is problematic, mainly due to the Privacy Law. An ISP or the state is prevented from intervening in content reaching the private customer.

“The state cannot force a private organization to defend itself. An example of change was recorded during the war, when the state issued an emergency regulation that allowed it to shut open web‑cams. That proved they understood the size of the problem, but this is an action that requires heavy regulation. Today, bodies in the country don’t have the tools needed to act based on intelligence information about exposed vulnerabilities.”

Do we need more aggressive regulation, or is a surgical‑case‑by‑case approach preferable?

“It’s better to start with awareness and lots of education. In large organizations like hospitals, the government should help financially and by providing guidelines and critical support when needed. The more serious problem is the private market, where there’s no organized body to work with, and it’s difficult to reach the citizen at the end. We need to raise awareness, and perhaps create a requirement for a minimum set of tools via cyber‑insurance companies.”